After a bit of a love-in over the Language Lovers competition last time out (don’t forget to vote!), today’s post takes a look at a specific translation example in order to analyse the translator’s role in creating meaning and the potential impact that our decisions can have.

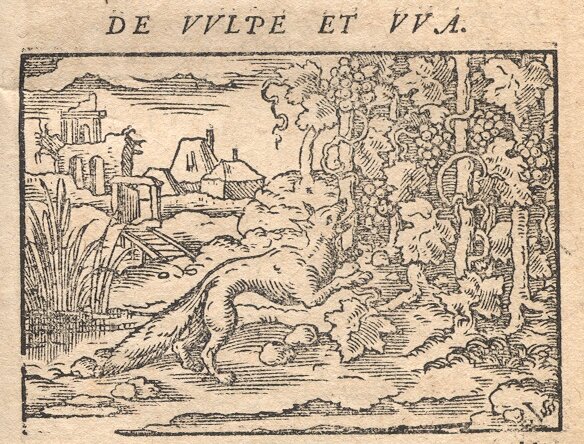

As the title suggests, the text chosen for analysis in this post is the famous fable of ‘The Fox and the Grapes’. First written (or more likely spoken) by Aesop in the 6th Century B.C., the fable has gone on to hold an important place in literary culture across the globe.

The definitive version of the fable as we know it here in England, translated by V.S. Vernon Jones in 1912, goes like this:

A hungry Fox saw some fine bunches of Grapes hanging from a vine that was trained along a high trellis, and did his best to reach them by jumping as high as he could into the air. But it was all in vain, for they were just out of reach: so he gave up trying, and walked away with an air of dignity and unconcern, remarking, “I thought those Grapes were ripe, but I see now they are quite sour.”

The moral that is most frequently taken from the story these days is that it is easy to take a dislike to something that you cannot have, and we do this in order to rationalise the fact that we do not have it whether or not that feeling is genuine.

Indeed, this moral is made explicit in many of the translations of the text, where authors have added a final remark outlining the fox’s real mental workings. French poet Isaac de Benserade, for example, adopts a thoughtful, moralising tone in his concise version and includes a final quatrain in which the fox admits that the grapes really were ripe but ‘what cannot be had, you speak of badly.’

So dominant is this interpretation of the fable that it is widely held that the English expression ‘sour grapes’ subsequently developed in relation to the usage in this tale. In contemporary English the phrase is used exactly as it is in the fable, referring to the act of pretending not to care for something you want but do not or cannot have.

What interests us from the context of translation, however, is the way in which a specific linguistic choice in the 1912 Vernon Jones translation has gone on to shape our understanding of the fable. As seen above, the grapes are described as ‘sour’ in the final line, yet research into earlier versions suggests that the Greek word employed in the original fables (‘ὄμφαξ’/’omphakes’) actually means ‘unripe’ grapes.

This interpretation is also alluded to in the Roman fabulist Phaedrus’ Latin version of the tale which pronounces: ‘nondum matura es’ [‘you are not ripe yet’], echoing the Greek original.

While initially appearing to be a minor change, upon closer inspection the use of the word ‘sour’ in fact alters the entire complexion of the story. In moving from ‘unripe’ (and therefore bad tasting as a result of this lack of maturity) to simply ‘sour’, we pass from a potential hint at patience and understanding on the part of the fox – he would perhaps return later at a more opportune moment when the grapes are ripe – to the disdainful, envious connotations that we have come to associate with the fable.

However, rather than being a mere slip on the part of the translator, this move represents a calculated choice that was designed to reflect the needs and the dominant ideology of the society into which the text was being translated. Beyond the aesthetic appeal that ‘sour grapes’ holds over the more clumsy ‘unripe grapes’, the term ‘unripe’ would have also contained the sexual connotation of an as-yet unripe woman, something that the author clearly sought to avoid in making his interpretation acceptable to the ultra-prudish audience of an approximately Victorian-era England.

The Greek phrasing not only contains this ambiguity – with the phrase having both the literal meaning of an unripe grape and the metaphorical usage of a girl not yet ripe for marriage – but is likely to have contained these sexual undertones as a fully intentional strand of meaning, with the original text existing in an age where advice against such actions would have perhaps had more pertinence. Given this centrality, the English author’s choice represents a clear attempt to sidestep what he deemed as an inappropriate interpretation.

In the canonical French translation of the fable by Jean de La Fontaine, meanwhile, which predates the English version by a considerable margin (it was first published in 1668) and was thus produced for both a different era and culture having its own different social standards and taboos, the rendering remains closer to the original version than the English does and leaves a greater amount of interpretive potential intact.

In rendering sour/unripe, La Fontaine used the phrase ‘ils sont trop verts’ [lit: ‘they are too green’ – ‘unripe’], and left ample room for interpretation.

Ultimately, in this specific context the example serves to demonstrate the power that translation wields in shaping meaning and exposes the way in which language use can be exploited to fulfil our own ideological wishes. More worryingly, perhaps, it demonstrates the extent to which we are often completely powerless to detect these changes: if we do not understand the language of the original then we are left at the mercy of the translator and take their rendering as the authoritative version.

Despite its continued relevance, the Vernon Jones version undeniably closes off several passages of meaning contained within the original while simultaneously opening up other channels which, while misrepresenting the source text, have nevertheless gone on to deeply ingrain themselves within English language and culture.

The power that the translator holds here is extraordinary: books, songs and films have subsequently emerged based on interpretations that developed from one man’s personal, culturally-bound take on an ancient text and the selection of one little word – ‘sour’.

Leave a comment